LEAFS TIME MACHINE: Golly Gee, It’s Howie Day in Canada!

By Toronto Suns Lance Hornby

One could spend all of Hockey Day In Canada recounting the Saturday night hijinks of Howie Meeker.

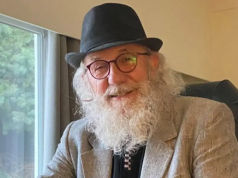

He and his tell-tale telestrator sadly left us in 2020, the oldest Maple Leaf at age 97, but Sportsnet’s Hockey Day show is giving a shout-out to the Parksville, B.C. resident as part of the Vancouver-Toronto game.

“Howie was an icon, he started it all in TV hockey analysis,” said Charlie Hodge, his close friend who wrote two books with Meeker, Golly Gee, It’s Me and Stop It There, Back It Up!.

“It could have been anyone, but he found a way to apply (the medium) to hockey. No one had taken the size of the rink, the many parts of the game and broken it all down, in a way viewers could understand.

“You appreciated the game was more than just the puck going in the net. He was famous for his hockey schools, too. He simply loved the game.

“His personality was unique, he had a rough charm about him, but unlike Don Cherry, he never said anything rude.”

Hodge describes Meeker as “a tough bugger” right to the end.

Putting his promising junior career in and around his native Kitchener, Ont., on hold, Meeker enlisted in the Canadian forces, nearly killed while training in England when a fellow soldier’s grenade accidentally landed at his feet.

“I’d have killed the bastard, but they transferred him first,” Meeker told the Toronto Sun at his Hockey Hall of Fame induction for the Foster Hewitt Award in 1998.

He survived his leg wounds and landed in France a year later.

Returning home, he won the 1947 Calder Trophy as rookie of the year with the Leafs, beating Gordie Howe among others, thanks in part to a five-goal game. After 185 points and four Stanley Cups up to 1951, Meeker kept playing while serving two years as Conservative Member of Parliament in Waterloo. After retiring, he coached the Leafs’ farm team in Pittsburgh to the 1955 Calder Cup, spent one year behind Toronto’s bench, the youngest in the league at the time, and was very briefly its general manager in 1957.

We say briefly because team exec Stafford Smythe made the mistake of shoving Meeker during a heated player personnel debate just before the

season began. Meeker decked him and stormed away without working one game, replaced by Punch Imlach, whom Meeker had scouted as his potential assistant.

There followed some wilderness years for Meeker, who yearned to teach the game. In the first chapter of Stop It There! he relayed to Hodge a recurring dream of playground shinny where all his teammates were out of position despite his warnings, leaving him to defend a 5-on-1.

Meeker finally found an outlet in running instruction camps, under contract to the government of Newfoundland. He dabbled in radio broadcast work for CJON in St. John’s, supplementing his income in sales and promotions for companies such as Toyota, Samsonite and Mattel Toys, but could not shake the feeling that fundamentals were being lost at both the amateur and pro level.

During a trip through Montreal in 1968 for a toy convention, he ran into Habs’ TV host Ted Darling, who needed a guest analyst for a game against visiting Chicago.

“I had no idea at the time what an amazing series of events was about to unfold when I first stuck on the headset,” Meeker wrote.

The squeaky-sounding sounding Meeker figured he might get only one shot, so why hold back his opinions?

“I’ve got the worst voice in the world, I can’t remember faces and names and they wanted to make me a colour analyst?’” Meeker told the Sun. “But I’d watched other guys do it. They were scared to say anything that would cost them their jobs. They said nothing instructional, nothing critical.”

Colour man Dick Irvin Jr. cringed when Meeker opened by insisting to the audience that multi-Cup winning defenceman J.C. Tremblay had messed up a play. But the next day producer Ralph Mellanby offered Meeker a regular seat.

That paired him with Dave Hodge in Toronto, in their powder blue HNIC jackets. Most fans loved Meeker’s theatrics and quaint exclamations such as ‘jiminy crickets’ and ‘gee willikers.’

“I grew up in an era where locker-room language was atrocious,” Meeker told the Sun. “If I’d used that on air, I’d have been fired, so I said something else. You’re like an actor. You do things to disturb

people. All I cared about was it would get them interested and talking about hockey.”

Meeker and the telestrator, a device allowing free-hand drawings over video, became inseparable.

“I said a prayer every night to thank it for saving my butt,” he said of on-air chirping the technicians to speed up, rewind, slow down or freeze the highlight. “My producer went nuts when I’d say it live and he’d get mad at the director. And the tape would always break.”

Meeker didn’t shy away on many issues, convinced Canada had learned too little from its near-defeat to Russia in the ’72 Summit Series: “What fools we are. The Canadian know-it-all attitude toward hockey is about as stubborn and stupid as the average male’s about asking for directions or reading a road map. It doesn’t happen until we are really lost.”

He expressed similar concerns in ‘98 when the country’s best crashed out of the Nagano Olympics.

Meanwhile, he and wife Grace had fallen in love with B.C. in the late 1970s after taking a fishing trip while there while attending a coaching clinic. After working Canucks games for BCTV, he retired in ’98, devoting time to favourite causes such as Special Olympics and guide dogs for the blind. He’s a Member of The Order of Canada.

“To me, he was a Dad, a mentor, so many things and taught me a lot of life lessons,” said Hodge, now a city councillor in Kelowna, B.C. “When the first book came out, we went to a lot of hotels, restaurants, and bars, where he was always signing autographs, never turning away a fan of any age. He’d be the oldest person at any rink we visited, but the last guy to leave.

“‘That’s what it’s all about kid,’” he’d tell me. “’The people.’”