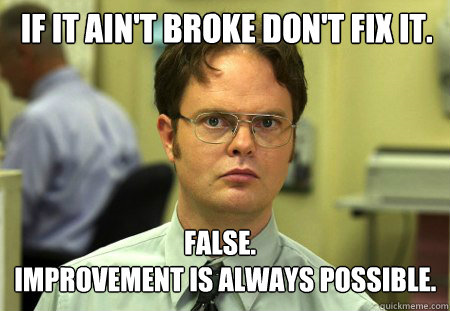

If something is broke, don’t fix it. This seems to be the apt mantra of doing business in the 21st century.

Our “systems” are the playthings of politicians and scientists and are notoriously elusive creatures to hold accountable or, for that matter, regulate in a way that promotes longevity. This, in my opinion, is one of the foremost challenges of any Democratic system.

During the 1970’s and 80’s, common sense dictated that, based on preliminary information, the Atlantic fishery was in trouble. Policy makers, rather than take a stand for posterity, assembled a task force to think about talking about what they might decide to do about it. Ultimately they threw their arms in the air claiming that the information they had at their disposal was inconclusive. As a result of this epic fence-sitting, it was business as usual where fishermen were concerned. Two years later the industry was dead and the remaining fish population was on life support and in very real palpable danger of breathing its last breath. Whether industry lobby was at fault or the monumental ineptitude of a system driven almost solely by monetary interests is a matter of opinion.

Our “systems” are the playthings of politicians and scientists and are notoriously elusive creatures to hold accountable or, for that matter, regulate in a way that promotes longevity.

Today, despite mounting compelling evidence in favour of global warming, the debate rages on, the opposing viewpoint populated mostly by industry zealots and paid lobby interests. Let’s be clear though: consumers – we, us – are not absolved. In April 2008, for instance, when the B.C. Government proposed new vehicle emission laws, Canadian consumers were asked if they would be willing to give up the drive-through option at many food and drink venues. Respondents replied with a resounding message: go after industry, go after other countries, but don’t mess with drive-through coffee. We care enough to give lip-service to the notion of global warming and the health of the environment but only as long as it doesn’t affect us directly. Such a notion as messing with fast food flies in the face of western capitalism and freedom.

These recent trends of forced part-time employment and the increasing numbers of Canadians living at or below the poverty line begs the need to ask why the government is fence-sitting on the issue… again.

Contrary to the notions of social philosophers like John Mill and Durkheim, that, given the opportunity, people will do the right thing, the answer may in fact lie with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Smith purports that government interference in economic policy should be disallowed.

Our perceived right to prosperity, it seems, overrides even the most obtuse common sense judgments based on factual evidence.

Dean Unger