Famous for the design and creation of the Gibson L50 , Lloyd Loar’s designs were known for precise tone, exquisite resonance, smooth aesthetics – all are the luthiers’ manna. The art and craft of any discipline can be learned…

…But, invariably, the adept will rise to the top, as Lloyd Allayre Loar did when he began his career at the Gibson-Mandolin Guitar Company, just after the turn of the century. Today, Loar is considered the forefather of the modern electric guitar, and the architect of what was to become the first American family of stringed instruments. But his career as a designer was marked with struggles and perdition of an unrecognized genius, slightly out of cadence with the rest of the world.

One of the great things to come out of the 19th century was vocational pride. Entrepreneurs had a firm handle on the notion of quality assurance, customer relationships and reputation – qualities that were not lost on Orville Gibson, luthier and founder of the Gibson Company. Orville sought out the best in the business to help bring his line of instruments to the forefront of the marketplace.

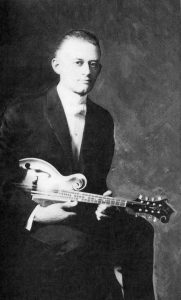

A native of Lewiston, Illinois, Loar was one of Gibson’s discoveries – a diamond in the rough. It was not long before Loar touched on his gifts. He was still quite young when he began demonstrating a keen interest in physics, geometry and music. In 1904, by eighteen, he had become a student and member of Ohio’s Oberlin Conservatory, where he studied orchestration, canon, counterpoint, fugue, and music theory with the anticipation and dedication of a studying sage.

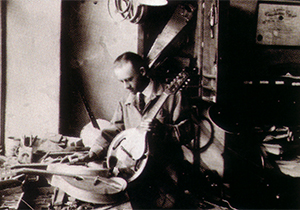

“Loar’s mind was ablaze with creative ideas, including his desire to improve the amplitude and tonal qualities on instruments other than the fretted, stringed variety.” Loar’s relationship with the Gibson company started early in his musical career. Well before he became an acoustic engineer, Loar worked for the company as a performer and composer.

By 1906 he had established a reputation as a professional concert musician, performing on Gibson Mandolins. It was later that same year when he met vocalist, Sally Fisher Shipp, of the Fisher Shipp Concert Company, who persuaded Loar to join their successful ensemble of Gibson sponsored musicians whose lot it was to demonstrate the pinnacle of Gibson design. By 1914 his passion and commitment had earned him the distinction of Concert Master for Gibson.

In 1918 he was hired as acoustic engineer and the following year became a design consultant. Through his critical thinking and problem solving, his drive to improve and perfect he played a key role in the design and development of the Gibson Master Model instruments developed between 1922 and 1924. These included the H-5 mandola, F-5 mandolin, K-5 mando- cello, style 5 banjos and the L5 Master Model guitar, possibly the most coveted among Gibson and vintage instrument collectors. Most instruments Loar crafted from late 1922 through December 1924 were personally hand-tested by Loar and carried his signature on the label, a mark of quality and distinction.

“Loar’s patents, letters, and drawings reveal a highly motivated thought process that never slept. He was always searching for what lay beyond truth and excellence,” explains Roger Siminoff, Loar historian, and former Editor of Frets Magazine. The excellence Loar achieved is parallel to the great violin makers, thelikes of Stradivarius, Amati, Guarneri; and guitar luthiers Christian Martin, Leo Fender and Orville Gibson himself. He did not as much seek to emulate their mastery in the development of his designs but strive beyond. Using elements of these early design styles and his knowledge of physics and the science of music itself, he incorporated fully graduated soundboards, backboards, and longitudinal tone bars, tuned f-holes, extended necks, elevated fret boards, increased neck pitch, and brought the concept of resonance tuning to a level of perfection not previously, or arguably, since, achieved in his realm of influence.

The excellence Loar achieved is parallel to the great violin makers, the likes of Stradivarius, Amati, Guarneri; and guitar luthiers Christian Martin, Leo Fender and Orville Gibson himself.

The excellence Loar achieved is parallel to the great violin makers, the likes of Stradivarius, Amati, Guarneri; and guitar luthiers Christian Martin, Leo Fender and Orville Gibson himself.

He believed that a quality instrument should not only have the strings perfectly tuned, but each structural component should be “tuned” to achieve perfect integration of the instrument as a whole. He reasoned that because every element was part of an integrated system, if one were not perfectly aligned, it would impinge or work contrary to another resulting in undesirable tones. To achieve this, Loar developed a system of tuning or adjusting his soundboards, backboards, tone bars, f-holes, and air chamber sizes so that each component resonated on a scale using concert pitch as its calibration point. Coupled with exquisite aesthetics, Loar’s structural tuning inspired creations that continue to stand alone in their class.

“Despite their prominence, the L-5 guitars were not considered a commercial success,” George Gruhn, of Gruhn Guitars explains, “The L-5 was ahead of its time. It came out while the banjo boom was at its pinnacle. The orchestral rhythm guitar had not yet emerged as an element of popular music.” As a result few were produced. It did, however, serve as a prototype for the D’Angelico, Stromberg, and Epiphone F-hole guitars to come in the early 1930’s that clearly emulated Loar’s L-5.

The signature label was used on the Master Model instruments

until 1924 when Loar left Gibson to strike out on his own, intent that with the help of investors he could propel stringed instrument technology into the future. After years of working with acoustics he believed amplification was the only reliable way to achieve consistency. And he was willing to stake his career on it.

“Loar’s mind was ablaze with creative ideas, including his desire to improve the amplitude and tonal qualities on other than fretted, stringed instruments,” writes Siminoff, “His ambitious nature appears to have been the greatest motivation for him to leave Gibson and explore other plateaus.”

A string of innovations would soon follow his departure, none of which would bear the rewards he realized at Gibson. The Gibson Company was a fertile proving ground, rich in established tradition and provided both a foundation and a leaping off point to incorporate his ideas. Like the L-5, many of his new, post-Gibson era concepts were not well received by the marketplace. Not because the ideas weren’t good, but in all likelihood because he was again ahead of his time. The world simply wasn’t ready for the direction he was headed.

Despite the reticence of the marketplace to embrace his ideas and the depression of the early 1930’s, Loar forged ahead with his plans. In 1933, he teamed up with a former co-worker at Gibson, Lewis Williams, and five local investors, to launch the Vivitone Company, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Now in a position to fully test his theory on electric amplification, he set about designing the Vivitone electric acoustic, a hybrid design that could be played with either acoustic or electric amplification, or both. With the advantage of historical perspective, it’s not hard to imagine this prototype being the predecessor to the modern-day electric guitar.

The Vivitone line included: mandolins, mandolas, mando-cellos, mando-basses, violins; violas, violin-cellos, double basses, Vivitone Claviers and Spanish, Hawaiian, tenor, and plectrum guitars. Most of these instruments were amplified employing Loar’s coil wound pickup design. On January 23,1934, three months after the formation of Vivitone, Loar, Moon, and Williams pursued a second round of financing. To accomplish this, they founded the Acousti-Lectric Company. Nevertheless, well into his years with Vivitone, the war with Germany had broken out and the wartime economy presented yet another set of challenges to the already struggling company.

The years 1927 to 1937 marked his most prolific design period with many patents being granted for various piano designs and keyboard actions, stringed instruments, and an electric coil-wound pickup he designed for the viola and string bass. The pick-up worked when the strings were plucked sending the vibrations through the bridge into the magnet and coil where they were transmitted via electric signal to an amplifier.

“His earliest instrument that featured this pickup was a solid-body viola that he built 10 years before the introduction of solid-body electric guitars,” Siminoff explains. “Lloyd strove to achieve power and amplitude in the instruments he designed, as a performing acoustic musician himself, he realized the frustrations of live performance. He was driven to find a solution to the vagaries of the acoustic performer, having a subjective bias.”

But lacking market vitality and a willing audience, the twilight of Lloyd Loar’s career was marked by hardship and exigency. “Loar’s contributions to acoustic and electric string music continue to go unrecognized by many,” writes Siminoff. “For the holder of Loar-signed instruments, his work lives on in the voice of the instrument itself. For luthiers who follow the art of mandolin and stringed instrument construction, there is nothing so pervasive as the goal of capturing that magical appearance and tone of an instrument from the Gibson/Loar era.”

Although he was appreciated in his time for his contributions, it was only through the lens of history and the longevity of his creations that he has become a legacy. Lloyd Loar revolutionized the way we think about the dynamics of sound today.

–Finis–